Reason #4080 that I love the Internet: it proves that your great grandfather was a socialist radical.

I’ve been in Florida for the past few days, visiting my 93-year-old grandmother Marie. One of my favorite pastimes is hearing her tell old family stories. This trip, her stories focused on her father, August Henkel. Gus, as he was known, was a working artist of German decent who lived in Queens, NY, back when Queens was more farmland than suburb. His lithographs hang throughout my grandmother’s house — beautiful, emotive scenes from another era. To his family, he was a gentle, wise, hard-working father of three. To the government, he was an enemy of the state.

Turns out my great grandfather was a pacifist and a free-thinker, at a time when war and conformity crushed dissent. He left his church, my grandmother told me, during World War I, when the hawkish pastor of his Lutheran congregation invoked a blessing on the guns of American soldiers. “The pastor literally had guns on the altar,” my grandmother told me, “and Gus watched him as he prayed that the guns would ‘find their targets and destroy their enemies.’ And Gus said to himself, ‘Can this be? How can this same man, who preaches about Jesus Christ, peace on earth and the brotherhood of men, how can he bless killing and destruction?’ Gus left and never came back.”

And that’s where my grandmother’s memory left off. But not the Internet’s.

A Google search on August Henkel reveals that Gus joined (or at least attended a service at) the Church of the Social Revolution in 1917. Remember, this was during the height of America’s war fever. Woodrow Wilson was ramming through the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, to stifle dissent in a time of war. Socialist, Communists and Wobblies everywhere were getting their heads cracked or spending time in jail. Not a great time to be a peacenik.

On a dramatic June Sunday in 1917, Gus participated in a peace ceremony at the Church of Social Revolution. The ceremony included boiling a cauldron of water and dumping in it flags from all over the world — literally, creating a “melting pot.” Gus thought this symbolized the common blood and brotherhood of all men. The US government thought it was treason.

Gus was tried, found guilty of desecrating the flag, and sentenced to a $100 fine and 30 days in the workhouse. He accepted the sentence with characteristically good cheer. “Oh well,” he apparently said. “That’s what happens when you have a capitalist press teaming up with a capitalist government.” And he managed to stay out of the headlines for the next 20 years.

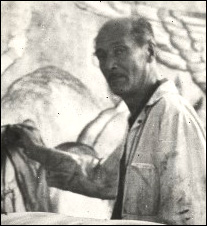

In 1939, Gus was working for the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration. The FAP was a Depression-era program that employed thousands of out-of-work artists, including giants like Jackson Pollack and Mark Rothko. Often, their jobs were to decorate public buildings with large-scale murals. Gus’s charge was Floyd Bennett Field, New York City’s first big airport. Inspired by aviators of history and mythology, Gus started in on a 900 square foot mural depicting the Wright Brothers, Lindbergh, Icarus, Earhart … and a man that looked a lot like Stalin. Oh, and a very prominent red star.

Was he trying to make a pro-communist declaration of hate against America? Or were the mustache’d strongman and red star simply artistic choices gone awry? My grandmother thinks the later. The US government thought the former. Once again, Gus went on trial — this time, primarily in the press — and was declared a red, a commie, a subversive, and any number of colorful invectives reserved for those who did not fully support America and its war effort. The murals were ripped down and burned. Gus never held a government contract again. The FAP was disbanded within a year.

My wife and I asked grandma Marie to describe the murals. Aside from their dimensions and general composition, and what we could all read in the press, there wasn’t much to say. Her memory didn’t reach back that far.

But the Internet’s did.

After just a few seconds of poking through the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art, we came upon three amazing old photographs of the Floyd Bennett Field murals in progress. One depicts Eugene Chodorow, Gus’s junior partner, painting the side of the enormous airplane hangar with an imposing propeller in the foreground. Another shows Chodorow standing at the same mural, with a young boy reclining on a plane’s wing and a hunched figure in the lower left corner. And the third shows Gus. Brush to the canvas, his intense eyes are set on the camera, somewhere between weary and determined. An artist at work. My great grandfather, the radical, at work.

I wake up every day and use the Internet for business, for play, for friends. I rarely use it to travel back in time. Today I did. And frankly, I’m relieved that the Internet has a better memory than me.

A few months ago, I realized that my generation will be the first for which

no history will be lost. All our records are digital. Barring a catastrophic breakdown of society, our progeny will be able to trace our digital footprints for centuries — indeed, for millennia — to come. After finding mere traces of my great grandfather, I’m left hungry for more. And also left glad that my great grandchildren will be able to find these exact footprints, the ones that I am leaving right now, on this peculiar time machine we call the Internet.